CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY

3.1 INTRODUCTION TO METHODS

The literature review above indicates that although much has been written on the inclusion of multimodality in education, the majority of the studies focus on multimodality in general and on its application to literacy teaching in K-12 settings. A few studies have focused on the inclusion of multimodality in high school and college writing courses, but not many academics are actually producing multimodal works; and few doctoral students so far have successfully defended multimodal dissertations, especially in the field of education. In spite of all the recent advances in technology, academic work is still predominantly done in the traditional print text format. The number of scholars who are actually trying to produce multimodal works is still limited. The same limitations and challenges are felt by doctoral students trying to produce multimodal dissertations, and facing countless obstacles from restrictions imposed by their advisory committees to specific requirements for depositing the work in the university archives.

The goal of this study is to expand the possibilities and the format of what a doctoral dissertation could look like, and question what counts as academic inquiry; to investigate the use of multimodality in doctoral dissertations in Education, and to offer some guidance to those wishing to pursue research in a multimodal form.

The primary research question for this study is to learn how have some doctoral candidates successfully overcome the problems/challenges typically encountered when trying to create and defend a multimodal doctoral dissertation in the field of education? I hope my investigation and analysis will help future doctoral students wishing to pursue multimodal research and dissertations.

In order to address the questions above, I conducted a case study, with multiple cases – locating four multimodal dissertations successfully defended in the last decade. Each case was selected based on the dissertation format itself and the modes included; following the pre-determined criteria detailed in the following sections. Interviews were conducted with the authors and their supervisors/ advisors, to learn from each case what were the factors involved and the challenges encountered along the way. The artifacts themselves (examined dissertations) were also analyzed for form and function.

3.2 RATIONALE FOR USING CASE STUDY

Before I go into the details and the particulars of my research, I would like to start by sharing a short video clip from SAGE Research Methods (Nind, 2017) talking about the need to innovate in research. This serves as an inspiration and a reminder for myself of what it means to remain curious and reflective as I embark on this journey, and I hope it might also serve as an inspiration to other colleagues who are also starting their own research study:

According to the definition and description of case study methodology proposed by Yin (2003), multiple case study is appropriate for this inquiry since the purpose and goal of the study is to investigate how each successful multimodal dissertation was able to be produced and how it overcame any obstacles encountered. Case study is suitable for this research because the total number of successfully defended multimodal dissertations is still extremely limited, and it would be impossible to conduct experimentation with a control group and controlled variables. In addition, the behavior of participants could not and should not be manipulated in the research process, and the context of each case is expected to be unique and relevant to the study, making case study an appropriate methodology choice for this investigation (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Hancock & Algozzine, 2006; Stake, 1995; Yin, 2003).

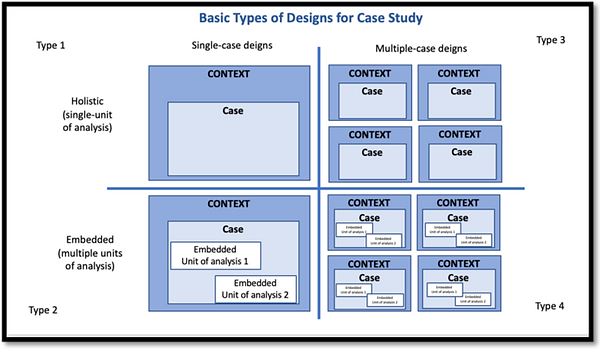

Yin (2003) identifies four types of case study: single or multiple case study designs, with holistic or embedded units of analysis. For this study, I will conduct a multiple-case design with multiple embedded units of analysis for each case - Type four in the graph below:

Figure 12: Yin (2003, p. 47)

This study consists of multiple case studies with successfully defended multimodal dissertations. I identified and located four different multimodal dissertations. For each case, I collected data from the dissertation itself; in addition, I conducted interviews with the individual authors plus their respective dissertation advisors. Multiple case study research allowed me to investigate within each case and across cases in order to understand the similarities and differences between the cases.

The following graphic from Yin (2003), provides a good visual representation of the steps involved in conducting a multiple case study. The graphic provides a nice visual representation of the steps and the procedure involved from the definition of the problem (research question) and selection of appropriate cases, to the setup and collection of data, to the final analysis and report:

Figure 13: Multiple Case Study Procedure - (Image source:Yin (2003, p. 58)

One of the typical characteristics of case study research, which I followed is the use of multiple data sources. I conducted interviews, in addition to reviewing the dissertation and the doctoral dissertation requirements from the respective university where the research was conducted. Because of the large amounts of data collected in this study, special attention was given to convey the findings in an understandable format to the reader; and to describe the context as well as the case itself (Stake, 1995; Yin, 2013).

The following video by SAGE Research Methods (2017) provides a nice short introduction to case study research for those who are new to this type of work. The video explains the origins of case study and some of the reasons researchers may choose to do case study, such as the ability to study a particular phenomenon in greater depth and the ability to combine different methods in the study. The video, however also warns the novice researcher of some of the potential weaknesses of case study, such as the length of time it may require and the potential for researcher bias when researchers become involved with their study participants, which can also lead to other ethical considerations that must be taken into consideration whenever human subjects are involved:

3.3 QUALITATIVE RESEARCH CONSIDERATIONS

While case studies may contain both qualitative and quantitative data, the study proposed here will be primarily qualitative in nature, following Stake’s (1995) considerations and explanation:

Qualitative research tries to establish an empathetic understanding for the reader. through description, sometimes thick description, conveying to the reader what experience itself would convey . . . Qualitative researchers treat, the uniqueness of individual cases and contexts as important to understanding. Particularization is an important aim, coming to know the particularity of the case. (p. 39)

Using qualitative research methods, this study is interested in exploring and understanding the individual perceptions and reasoning of each target case and their authors. Through thick description, explained in the next section, I will endeavor to reach a deep understanding of each case and maintain a reflective role with continuous interpretation and ongoing investigation (Stake, 1995; Schwandt & Gates, 2018).

This study follows postmodern, constructivist, qualitative research principles and beliefs that: 1. Reality is socially constructed and researchers are integral part of the research context; 2. Research is conducted in a reflexive self-critical, creative dialogue; 3. The investigation is a process where the issues may emerge out of the questioning and should be interpreted within the context in which they take place. The role of the researcher in this context is to interpret the findings – as new themes emerge and require interpretation, new research instruments are required and created for the specifics of the study at hand (Holliday, 2016).

In this framework, research rigor is achieved through principled development of research strategy to suit the scenario being studied as it is designed and developed. The researcher must remain open and attentive to the research questions and the development of data collection and fieldwork to ensure that the unexpected is able to emerge and be made relevant. The researcher must remain flexible and maintain a reflexive stance to acknowledge the emergence of new topics and new meanings. Using thick description, the researcher is able to delve into the heart of the issues to capture their essence (Holliday, 2016; Denzin & Lincoln, 2018; Ponterotto, 2006).

Schwandt & Gates (2018) remind us of the continuous expansion of qualitative research methods and what it means to use case study as a form of inquiry that can include different modes of reasoning and remain flexible and responsive to the particulars of the research question and the goals of the researcher. In the following video, Schwandt (2011) talks about his work and interests, including the creation of the Dictionary of Qualitative Research and the pursuit of qualitative research at the University of Illinois. He describes the importance of understanding the terminology and the foundations of what it means to conduct qualitative research, which is of particular interest for the pursuit of my own research:

Schwandt (2011) reminds us of the need to take a reflexive approach to research and he challenges the researcher to question and understand the foundations of qualitative inquiry. He presses the researcher to seek “a different way of knowing,” which I hope to be able to explore in this study – remaining inquisitive, reflexive, and open to new ways of knowing.

Denzin & Lincoln (2018) stress the flexible and open-ended nature of the qualitative research methodology and how the researcher should resist the temptation to impose a single, unilateral perspective over the entire study. In the postmodern research framework, the researcher assumes a role of co-creator of the study and understands that the researcher “does not own” the data or the right to make assumptions about those being studied. Subjects can and do challenge how they are portrayed and written about (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

In the following video, Lincoln (2018) talks about some of the trends and some of her hopes for what is developing in the field of research today. She speculates what the future of qualitative research might look like and stresses the need to add more "voices from the fringes:"

The message from Lincoln (2018) above is very inspiring when she talks about the need to include the voices from the margins. Although my work does not address minorities and indigenous populations directly, I do hope that the study and inclusion of multimodality in academia can become one small piece of the puzzle of giving voice to a larger segment of the population, who might otherwise not have a way of expression. I hope to contribute to providing alternative means of expression and enabling the inclusion of more voices in academic work.

3.4 THICK DESCRIPTION

This study seeks to gain a deep understanding of the cases identified and offer a "thick description" of each case and each participant interview. My intent is to identify the reasons, challenges and interpretations of each interviewee in their own words and also gain an understanding of the context of each case - not necessarily looking for cause and effect, but rather looking for an interpretation co-constructed with the participants. The goal is not just to produce a large amount of data, but rather focusing on the interpretation of meaning and context (Ponterotto, 2006; Brinkmann, 2018).

The basis for the concept of thick description I intend to follow in this study comes in part from the anthropologist Geertz (1973), who distinguished "thick description' from "thin description" which is a simple factual account of facts and behavior without much interpretation. In contrast, thick description seeks to interpret the behavior within its cultural context. Geertz (1973), uses the example of a wink which can be seen as just a contraction of the eyelids (pure description of the behavior without interpretation), or it can be seen as a sign which carries meaning and must be interpreted within its cultural context (in search of a thick description). It is not enough to describe what someone or a group does, one has to look deeper to try to understand the phenomenon within the culture and the context in which it takes place (Ponterotto, 2006).

In the following video, Geertz (2006) talks about his love for fieldwork and talks about his interests and the driving force behind his interests and his study. In this video, he does not use the term "thick description," but simply talks about his interest in studying different cultures and groups, and how he believes this type of study should be conducted:

In watching the video, I am particularly interested in Geertz’s idea of not necessarily trying to find generalities or abstract commonalities, but rather looking for the specifics of each case, looking for how they are different, and what is specific and extraordinary about the subject of study. Geertz’s approach to seeking a deep understanding of the subject will be very instrumental in my proposed study.

A thick description . . . does more than record what a person is doing. It goes beyond mere fact and surface appearances. It presents detail, context, emotion, and the webs of social relationships that join persons to one another. Thick description evokes emotionality and self-feelings. It inserts history into experience. It establishes the significance of an experience, or the sequence of events, for the person or persons in question. In thick description, the voices, feelings, actions, and meanings of interacting individuals are heard.” (Ponterotto, 2006; p. 540)

But, Ponterotto (2006) warns that thick description involves more than just collecting great detail and large amounts of data. Thick description involves considerations of the context and meaning as well as interpreting participant intentions in their behaviors and actions. It is the qualitative researcher’s task to thickly describe social action, so that thick interpretations can be made. Below are some of the essential components of thick description offered by Ponterotto (2006):

Thick description involves the interpretation of social behavior within the context in which it takes place.

Thick description attempts to capture the thoughts, emotions and interactions of study participants.

Thick description interpretation entails assigning motivation and intention on the part of the participants.

The context and details of the study are carefully described by the researcher to enable the reader to get a sense of ‘having been there’ themselves;

Thick description calls for thick interpretation, which hopefully in turn leads to thick meaning.

3.5 ADDITIONAL METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Denzin and Lincoln (2018) discuss the need for research to remain flexible and embrace multiplicity, which I hope to follow in this study. One of the concepts explored by Denzin and Lincoln (2018) is the Bricolage – the term was first introduced by the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss – and later proposed as an attempt to bring a range of techniques and principles from different disciplines to present research finding in new ways that may not be explained exclusively using a single method.

. . . the researcher works as a person who assembles pieces as a quilt maker, where the collection of different pieces when put together provide the big picture of the situation or phenomenon. The bricoleur (researcher) is a “jack of all trades” and the research practice is pragmatic and self-reflexive – and sometimes new tools and techniques have to be invented for the particular needs of a particular study . . . the choice of which interpretive practices to employ is not necessarily set in advance. The choice of research practices depends upon the questions that are asked, and the questions depend on their context, what is available in the context, and what the researcher can do in that setting. (p. 5)

The need for flexibility and the idea of weaving together different techniques from different disciplines will be important in this study as it will bring together elements of case study with interviews and thick description, brought together with elements from critical research and multimodal and visual research. And at the same time, questioning and trying to push the boundaries of the traditional doctoral dissertation and what counts as research. It is in this vein that I propose to borrow some of the ideas and characteristics of Bricolage as proposed by Denzin and Lincoln (2018).

Working with multimodality begs the researcher to remain open and flexible to increased diversity of experiences and may require the need for new theories that can accommodate and embrace this diversity and have the flexibility to change and grow as the study progresses. Kincheloe et al. (2018) draws his inspiration from Freire’s critical pedagogy that I would also like to invoke for this study.

Kincheloe (2013) admits that critical theory is not one unified theory, but it follows some underlying assumptions that I will also keep in this research: 1. there is no value-free science; 2. all research is socially and historically situated and constructed and mediated by power relations that must be acknowledged by the researcher; 3. facts are never isolated from the values and ideological context in which they occur; 3. all power relations are mediated through language and the context in which they take place; 4. the researcher must remain cautious of the role of the researcher and when and how to resist the maintenance and reproduction of current entrenched systems.

In this study I use the term Bricolage to describe the practice of research that is eclectic, hybrid, and derives from an interdisciplinary approach, piecing together elements from a variety of sources, forms, and disciplines. Bricolage is used here with a focus on flexibility and multiplicity. In this interpretation of bricolage, there is no one correct telling, each telling reflects a different perspective. Research is viewed as a process shaped by the researcher’s own position in the world. This subjectivity requires self-awareness and reflexivity on the part of the researcher for a continual evaluation of the research – recognizing how the researcher and participants actively co-construct knowledge. And based on the notion that as the research progresses it is then further refined in a continuous loop. Bricolage provides a deep, rich and yet fluid analysis, where the choices regarding which interpretive practice to employ are not necessarily made in advance (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018; Kincheloe et al., 2018; Rogers, 2012).

In the following video, Kincheloe (2013) explains the notion of Critical Pedagogy and its importance to education around the world today, inspired by the work of Freire. The author also discusses the notion of what it means to be "normal" in education and the need to fight against it in scholarship work:

Kincheloe’s words echo much of the impetus that drives this work – he questions what is the role of pedagogy, not just in elementary education, but also in producing scholarly work. He stresses the need to have an evolving critical pedagogy that embraces new discourses and new ideas, challenging current practices, and the need to make people conform to the “normal.” This work is an attempt to question and challenge the notion of what is considered normal in dissertation and academic writing and an attempt to construct a different notion of scholarship.

Academic research in general and qualitative research methods in particular, have evolved through time from early positivism and post-positivism to the more current postmodern paradigm (Ponterotto, 2006; Holliday 2016; Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). The researcher must now remain open and critical of his/her own role as co-creator of meaning. Within the postmodern paradigm, the researcher employs whatever means seem appropriate to get to the understandings that we seek (Holliday, 2016; Denzin & Lincoln, 2000). “We are in a new age where messy, uncertain multi-voiced texts, cultural criticism, and new experimental works will become more common, as will more reflexive forms of fieldwork, analysis, and intertextual representation” (Schwandt & Gates, 2018, p.15).

This video shows Dr. Norman Denzin's (2014) interview, where he expresses his views on some of the important directions and future trends of qualitative research and also discusses the politics of how ethics boards limit qualitative research methodology (and the need to push back!)

In the video, Denzin makes the important case that science is part of a moral and political discourse, and how the researcher must be aware of how their study may or may not conform to the current trends and types of research being funded and considered acceptable by universities. As a novice researcher, it is encouraging to hear Denzin speak of the need to question from within the notion of science and methodology and the need to look at the moral and ethical implications of the work we do – not imposed from the outside, but rather emerging from within and understanding how ethics, inquiry, and science are weaved together.

I find the notion of Critical Research and Bricolage to be in alignment with the principles and theoretical underpinnings of my work with multimodality. Critical Research is deeply rooted in Freire's Critical Pedagogy, and it corroborates the proposition to include multimodality in education. Critical Pedagogy is concerned with questioning the status quo and challenging the traditional ways of academic work. In working with multimodality, it is partly my hope to contribute, even if in a small way, to the expansion of the notion of scholarship. I expect to continue to explore the notion of the Bricoleur and the need for embracing interdisciplinarity in my research study.

Anderson, Stewart, & Aziz (2016) juxtapose multimodality and ethnography – multimodality as meaning making through multiple modes; and ethnography as a way to situate meaning according to a specific perspective. Multimodality is not to be taken as a singular theory, but rather as an approach and a way of working using multiple modes. For Anderson, Stewart, & Aziz (2016), scholars working with multimodality should be mindful of accounting for different vantage points; different ways of seeing the world, and taking advantage of multiple methodologies depending on the research questions and goals.

3.6 VISUAL RESEARCH CONSIDERATIONS

The focus of this work is the use of multimodality in academic and dissertation writing, thus many of the concepts explored in visual research will be significant to this study, making sure to include and explore the affordances of video. I do expect and hope to be able to video record the interviews and will have to consider the technical options and implications involved. Not just “talking about” multimodality, but rather working with and through multimodal resources.

Margolis & Zunjarwad (2018) recognize the existence of multiple perspectives in producing and analyzing multimodal research: 1. research can focus both on the study of participant-produced and researcher-produced visual data; 2. visual data may or may not be produced for the purpose of research; 3. visual data can also be used to communicate the research findings.

Among the many types and possibilities of multimodal text, photography has long been used in research to serve as evidence and illustration to the work being described in written form, especially in fields like anthropology, art and even medicine. In the last few decades, however, new technologies have enabled users to begin producing and recording every moment of their lives using their cellphone cameras (Ball, 2004; Literat et al., 2018; Margolis & Zunjarwad, 2018).

The current digital landscape has greatly expanded the ease and availability of photographs and video recording to both the researcher and the participants of research. Advances in technology are now creating new possibilities and new relationship dynamics between researcher, participant and also readers. In this context, visual research continues to grow and become more interdisciplinary. The addition of video and film to research interactions, and the ability to review, stop and replay recordings, has created new possibilities and new challenges for researchers (Jewitt, 2012; Margolis & Zunjarwad, 2018).

Making and analyzing still or moving pictures brings on a whole new set of complexity and challenges for the researcher . . . the ability to record social action for later detailed examination is facilitated by video, but presenting video creates a whole new set of issues: If researchers are to present their ethnography visually, then alongside the skills of photographer or videographer, they need skills in visual communication, media literacy, and editing. (Margolis & Zunjarwad, 2018, p. 1043)

The new technological advances also raise new questions and challenges regarding issues of ethics, confidentiality, access, copyright, informed consent, and new ways of sharing information (Archer, 2017; Ball, 2004; Margolis & Zunjarwad, 2018).

Another important aspect of the new affordances brought about by new technological advances is the possibility to present information and data in non-linear form. This allows the viewer or the reader to explore the information following different paths according to their interests and needs. All these considerations and all the new possibilities created by the inclusion of multimodality in academic discourse broaden the possibilities for how research is conducted, analyzed and shared (Ball, 2004; Margolis & Zunjarwad, 2018).

The following video by Salmos (2017) with the SAGE Research Online, discusses some of the new possibilities currently available for researchers using technology in visual research:

I expect to explore some of the possibilities new technology offers me as a researcher. Video conferencing will allow me to conduct interviews with participants, regardless of their physical location. With currently available technology, scheduling and time zone differences will be the only limitations to being able to invite participants from around the world. And by recording the interviews, I hope to be able to use the recorded interviews to show the ideas and statements as intended by the respondent, in their own voice.

3.7 ETHNOGRAPHY

This study also employs elements of auto-ethnography, since the author is attempting to produce a multimodal dissertation to investigate the use of multimodality in dissertation writing. Ethnography tools allow the researcher to become immersed in the phenomenon being studied, and to reflect on the process of creating a multimodal dissertation.

Traditionally, ethnography has been a common method in anthropology, but now being employed by researchers in a variety of fields. Ethnography takes a less impersonal approach to research due to the nature of the work, discussion, and analysis of personal experiences, feelings, and perceptions of individuals and self. Ethnography is not limited to making observations; it also attempts to explain the phenomena observed in a structured, narrative way, drawing on the theory, but also on direct experience and intuitions, which may contradict previously held assumptions. Here the researcher’s own feelings and experiences are incorporated into the story and speaking directly to the reader, rather than keeping a more neutral position and language. (Ellis et al. 2011; Anderson, 2006; Heath et al. 2008). This ethnographic approach requires ongoing analysis, comparing, reflecting, assessing, and “coming to feel” (Heath et al. 2008). And the aim is to provide insightful descriptions based on theoretical assumptions (Hammersley, 1990, 2018).

One of the dangers to be kept in mind when conducting ethnographic research is bias, since it involves subjective interpretation and in this particular case, since the researcher is herself, embedded in the study being conducted. The researcher takes an active role in the participation, analysis, and production of the activities and objects under study (Hammersley, 1990, 2017; Heath et al, 2008). The value of ethnographic work often depends on showing that the particular events described instantiate something of general significance about the social world. The study of one case, may not be generalizable to the entire world. The task of distinguishing universal principles from one another and from their contexts is very difficult, if not impossible when studying a single case or a small number of cases (Hammersley, 2018). Hammersley (1990) warns of the fact that all phenomena can provide numerous, equally true descriptions of any scene or behavior. How one describes an object on any particular occasion depends on what one takes to be relevant. Yet, descriptions are always from a particular, value-based point of view.

3.8 CONSIDERATIONS ON INTERVIEWING

For this study, semi-structured interviews were used. Because of the nature and the goal of this research and the fact that each case generated unique and different information and data, a pre-set and completely structured interview would not produce the most complete desired outcome; but at the same time, some structure and direction was needed to ensure the minimum desired information is collected and addressed. Brinkmann (2018) reminds us:

… in human interactions it is often impossible to know in advance the issues or ideas that may come up, but some direction may be necessary to address and fully explore the research question. (p. 990)

Semi-structured interviews allow the researcher and participants to explore and have sufficient flexibility to follow on different leads and angles deemed important at the moment (Brinkmann, 2018). This, of course, demands careful preparation and reflection of how to involve interviewees actively, how to avoid leading the discussion or the answers and how to engage the interviewee in a way to bring insightful perspectives to light (Brinkmann, 2018; Stake, 1995; Yin, 2006).

When conducting interviews, it is critical for the researcher to consider the role of the interviewer and take into account the purpose of the interview, the possible power relations taking place during the interview, and any ethical issues that may arise from the study. The interviewer is never neutral and must be careful when attempting to interpret and explain participants' responses. The interview must always be viewed in its proper sociocultural context, taking into account the role of the interviewer in the study dynamic. In this regard, the researcher must be keenly aware of the importance of physical factors that may affect or impact the outcomes of the interview, such as setting, time, and technology constraints (Brinkmann, 2018; Denzin and Lincoln, 2018; Kincheloe et al., 2018; Stake, 1995).

The following video by Gardner (2018), gives a nice short overview of some key concepts and ideas about qualitative research interviewing:

The video serves as a good reminder of some critical considerations to conducting qualitative interviews, and the need for preparation prior to the actual interview – knowing what to ask and when to be quiet, learning to listen and to allow the ideas to emerge, and knowing how to follow up and draw out critical aspects of the topic at hand. It is important to understand how the interview is co-produced with the participants and how our own position affects and influences the interview. But Gardner also warns us of the need to remain open and be prepared for the unexpected.